.png)

.png) Pteranodon is a large pteranodontid pterosaur native to much of the North American Midwest during the late Cretaceous period, 88 to 80.5 million years ago. At the time, this area was a large shallow ocean called the Western Interior Seaway. They are among the largest known pterosaurs, and are notable for their extremely distinct sexual dimorphism.

Pteranodon is a large pteranodontid pterosaur native to much of the North American Midwest during the late Cretaceous period, 88 to 80.5 million years ago. At the time, this area was a large shallow ocean called the Western Interior Seaway. They are among the largest known pterosaurs, and are notable for their extremely distinct sexual dimorphism.

The first remains were found in the Smoky Hills Chalk of western Kansas by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1870, and named by Marsh in 1871. It was the first pterosaur to be discovered outside of Europe by paleontologists, and was originally named Pterodactylus oweni. However, that species name was already occupied (though it has since been reclassified), so Marsh renamed his discovery Pterodactylus occidentalis. He also named the largest specimen Pterodactylus ingens, and the smallest specimen Pterodactylus velox. The remains consisted mostly of wing bones.

Around the same time, Marsh’s rival Edward Drinker Cope discovered wing bone fossils which he assigned to the genus Ornithocheirus (though he misspelled the name as Ornithochirus). He named two species, Ornithochirus umbrosus and Ornithochirus harpyia. The paper naming these species was published in 1872, only five days after Marsh’s. As the rivals recognized that the fossils they had named belonged to the same species, debate occurred over which name should be given priority. In 1875, Cope relented and allowed Marsh’s classification to take priority, but maintained that the umbrosus species was distinct from Marsh’s other species of Pterodactylus. Later paleontologists would disagree with Cope’s conclusion, determining that P. umbrosus was not a distinct species.

On May 2, 1876, Samuel Wendell Williston discovered the first-known skull of the animal near the Smoky Hill River in Kansas. Shortly after, a smaller skull was also discovered. Williston alerted Marsh, his employer, to the discovery; Marsh noted that the skull lacked teeth and possessed a bony crest on the head. These features were distinctly different from other known pterosaurs at the time, prompting Marsh to reclassify the animal. No longer a member of Pterodactylus, the genus was christened Pteranodon, meaning “wing without teeth.” The species recognized at the time included Pteranodon occidentalis and Pteranodon ingens, along with the newly-named Pteranodon longiceps; the specific epithet of this new species refers to the length of its skull.

On May 2, 1876, Samuel Wendell Williston discovered the first-known skull of the animal near the Smoky Hill River in Kansas. Shortly after, a smaller skull was also discovered. Williston alerted Marsh, his employer, to the discovery; Marsh noted that the skull lacked teeth and possessed a bony crest on the head. These features were distinctly different from other known pterosaurs at the time, prompting Marsh to reclassify the animal. No longer a member of Pterodactylus, the genus was christened Pteranodon, meaning “wing without teeth.” The species recognized at the time included Pteranodon occidentalis and Pteranodon ingens, along with the newly-named Pteranodon longiceps; the specific epithet of this new species refers to the length of its skull.

Three other species Marsh named at the time included Pteranodon comptus, Pteranodon nanus, and Pteranodon gracilis. The final of those three was named based on a wing bone which he had mistaken for a pelvic bone. He recognized his mistake, however, and reclassified it as Nyctosaurus gracilis.

Samuel Williston would return to question the classification of all Pteranodon genera beginning in 1892. He had learned of toothless pterosaur jaws discovered in England’s Cambridge Greensand which were assigned to the genus Ornithostoma, and suggested that Pteranodon should also be given this name as it was discovered later. This decision was never formally accepted, however. In the end, the two names were recognized as separate genera, and neither incorporated the other. At one point, Williston believed that there could be seven Pteranodon species; as of 1903, he narrowed this down to just three species. These were the small P. velox, medium-sized P. occidentalis, and large P. ingens. Both P. comptus and P. nanus were reclassified as Nyctosaurus, and Williston considered P. longiceps to potentially be the same species as either P. velox or P. occidentalis.

In 1910, the classification of Pteranodon species would be challenged yet again. George Francis Eaton was the first scientist to describe the whole skeleton of the animal, using this information to determine that Pteranodon longiceps was a valid species and Pteranodon velox was not. This three-species conclusion was upheld for decades.

In 1910, the classification of Pteranodon species would be challenged yet again. George Francis Eaton was the first scientist to describe the whole skeleton of the animal, using this information to determine that Pteranodon longiceps was a valid species and Pteranodon velox was not. This three-species conclusion was upheld for decades.

The discovery of a new species by George F. Sternberg in 1952, named Pteranodon sternbergi later in 1966 complicated the situation, as it was found to have a prominent upright crest. As many of the skeletons were headless, paleontologist Halsey Wilkinson Miller argued in 1972 that only the fossils that had known skulls (Pteranodon longiceps and Pteranodon sternbergi) should be considered valid species. Eaton and Miller would go on to name several other species, assigning them into three subgenera. First, the long-crested species P. longiceps and P. ingens, which was renamed as P. marshi, were classified in the Pteranodon subgenus. Second, the tall-crested species P. sternbergi and the newly-named P. walkeri were classified in the subgenus Geosternbergia. Third, P. occidentalis was renamed as P. eatoni and classified in the subgenus Occidentalia.

Today, the only recognized genus is Pteranodon longiceps. In 2010, Alexander W.A. Kellner reclassified P. sternbergi as Geosternbergia sternbergi, and also named a new species Geosternbergia maiseyi. Paleontologist S. Christopher Bennett has suggested that Geosternbergia, which originated slightly earlier in time, evolved directly into Pteranodon.

Throughout the history of paleontology, around 1,200 Pteranodon fossils have been discovered in Kansas, Alabama, Nebraska, Wyoming, and South Dakota. This makes it more common than any other known pterosaur in the fossil record. Some possible Pteranodon remains are known from Skåne, Sweden and from the East Coast of North America.

Throughout the history of paleontology, around 1,200 Pteranodon fossils have been discovered in Kansas, Alabama, Nebraska, Wyoming, and South Dakota. This makes it more common than any other known pterosaur in the fossil record. Some possible Pteranodon remains are known from Skåne, Sweden and from the East Coast of North America.

International Genetic Technologies cloned the first Pteranodon sometime between 1986 and 1993, along with Geosternbergia, which at the time was classified as Pteranodon. At least three variants of Pteranodon have been created, which Jurassic-Pedia has classified as three subspecies for the sake of clarity. The subspecies are Pteranodon longiceps longiceps, which is believed to be the original cloned variant and is quite rare; Pteranodon longiceps hippocratesi, an aberrant subspecies with teeth; and finally Pteranodon longiceps masranii, which was first hatched in 2004 or 2005 and is by far the most common. This final subspecies is anatomically very similar to those in the fossil record, leading to some suggestions that it has the greatest proportion of unaltered ancestral P. longiceps genes.

Description

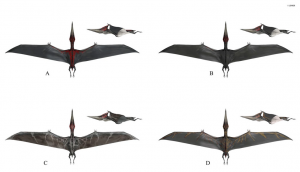

All of the subspecies described here have similar features. They are members of the family Pteranodontidae, which itself is a part of the pterosaur suborder Pterodactyloidea. This means that they are among the short-tailed pterosaurs. In all three, the beak is quite long and has a pointed tip; the sharpest and widest belongs to P. l. masranii, while the beak of P. l. longiceps has a slightly hooked end rather like a fish-eating bird’s. The head and neck differ between the pterosaurs in a few other notable ways, though the overall anatomy is similar. The most obvious difference are the small, triangular teeth of P. l. hippocratesi; these are an aberrant feature, and are presumed to be the result of genetic engineering (intentional or accidental). The head crests differ between the three P. longiceps subspecies. In Pteranodon, the head crest is roughly triangular and points backward from the skull; in fossil specimens, the female’s crest is much smaller, but at least P. l. hippocratesi, they appear to have been engineered to be more or less equal in size. In P. l. masranii, the females’ crests are much smaller than those of the males, more like fossil Pteranodons. The head crest of P. l. longiceps is narrower and slightly bent, while P. l. hippocratesi has a mostly straight crest. In all three, the tongue is narrow and pointed, and does not appear able to extend out of the beak. The nostrils are located near the base of the beak, on the upper side.

Size varies among these pterosaurs. Below is a list of each of their physical dimensions, including all three subspecies of Pteranodon longiceps and its fossil ancestors.

- Fossil Pteranodon longiceps

- Male

- Wingspan: 5.6m (18ft) to 6.25m (20.5ft)

- Length: 2.4m (8ft)

- Weight: Debated; estimates range from 20kg (44lbs) to 93kg (205lbs)

- Female

- Wingspan: 3.8m (12ft)

- Length: 1.6m (5.3ft)

- Weight: Unknown, but lighter than the male

- Male

- Pteranodon longiceps longiceps

- Male (?)

- Wingspan: 7.6m (25ft)

- Length: 3m (10ft)

- Weight: Unknown

- Female

- Wingspan: Unknown

- Length: Unknown

- Weight: Unknown

- Male (?)

- Pteranodon longiceps hippocratesi

- Male

- Wingspan: At least 9.8m (32ft); 14m (45.9ft) in some 2001 sources

- Length: At least 3m (10.2ft)

- Weight: 81.6kg (180lbs) in some 2001 sources; 226.8kg (500lbs) to 272.2kg (600lbs), according to Flyers

- Female

- Wingspan: 9.1m (30ft) to 9.8m (32ft)

- Length: 3m (10.2ft)

- Weight: 54.4kg (120lbs) in some 2001 sources

- Male

- Pteranodon longiceps masranii

- Male

- Wingspan: 7.9m (26ft) to 10.1m (33ft), according to Jurassic World: The Game

- Length: Presumably about 3.8m (12.3ft) based on female’s proportions

- Weight: Presumably about 48.9kg (107.8lbs) based on female’s proportions

- Female

- Wingspan: 5.5m (18ft) to 6m (19.8ft); may reach 7.5m (24.6ft) according to Jurassic World social media

- Length: 2.4m (8ft) to 3.1m (10.2ft)

- Weight: 30kg (66.1lbs) to 31.8kg (70lbs)

- Male

The neck is long and somewhat flexible, though much of its body consists of the large wings. Size among the Pteranodon longiceps subspecies is variable. In the fossil record, the male of this animal reached wingspans of 5.6 meters (18 feet) to 6.25 meters (20.5 feet); female P. l. masranii reach similar sizes, though fossil females have wingspans of only 3.8 meters (12 feet). What are presumed to be male P. l. longiceps are somewhat larger than female P. l. masranii, while female P. l. hippocratesi have broader wingspans yet. They are also the heaviest subspecies, with males weighing five to six hundred pounds according to Flyers. In the Jurassic Park /// arcade game, Jurassic Park ///: Park Builder, and the Jurassic Park /// Field Guide, the male (referred to as “Giant Pteranodon“) is much larger than the females, having a 14-meter (45.9-foot) wingspan according to the latter two.

Fossil Pteranodon longiceps are estimated to weigh between 20 kilograms (44 pounds) to 93 kilograms (205 pounds) in adult males; P. l. masranii females weigh 66 to 70 pounds as adults. In contrast to the junior novels, the Jurassic Park /// Field Guide lists “giant” Pteranodons as weighing 180 pounds, though it still gives them 45-foot wingspans. The standard Pteranodon is said to have a 30-foot wingspan and weighs 120 pounds. According to the mobile application Jurassic World Facts, the body length of a Pteranodon is about eight feet and the wingspan is twenty-four feet (a different entry claims it is 24.6 feet); it is unclear which subspecies this is meant to refer to. The mobile game Jurassic World: The Game, which features what appears to be a male P. l. masranii, describes their wingspan as ranging from twenty-six to thirty-three feet, which would make it larger than any Pteranodon known in the fossil record. Despite this, the game’s fact file claims that P. l. masranii is most similar to fossil specimens out of all three subspecies.

When standing on all fours, an average adult Pteranodon is roughly as tall as a human, though some can easily grow to a larger size than this.

The wings of Pteranodon are formed from the arm bones, as with all pterosaurs. The majority of the wing membrane, called the brachiopatagium, stretches from the tip of the fourth finger to the hips. In addition, all subspecies have a smaller membrane called a propatagium which stretches between the shoulder and the elbow. There are three exposed fingers, as well as the fourth one that supports the wing. The membrane is muscular in order to allow the animal to achieve powered flight. Part of the membrane stretches to the tail, though this is not particularly prominent; this membrane is called the uropatagium. The tail itself is short and stiff, and reaches up to 25 centimeters (9.8 inches) long. Wing morphology differs between InGen’s pterosaurs and their fossil counterparts; the wings of fossil pterosaurs have rounded tips, while InGen’s have narrow, pointed wingtips. Overall, InGen’s pterosaurs have less membrane surface area than the extinct versions, which may increase the effort required to remain airborne.

The legs and feet are substantially different than those of fossil pterosaurs, having very bird-like anatomy that permits them to grasp. Pteranodon has been known to do this extensively, whether it is to perch bipedally or grab prey items. The legs are very muscular, and the feet have four toes; one of these resembles a thumb. When walking, they use a quadruped gait, with the wing finger held upward. Flight in fossil pterosaurs was achieved by pushing off with the wings from a quadrupedal position; InGen’s pterosaurs use a variety of other methods to achieve flight, such as standing on two legs and jumping while forcefully flapping the wings, or standing into the wind and spreading the wings wide. Why they opt to use these more energy-consuming methods is unknown, but may be a result of their altered leg and wing anatomy. According to the mobile application Jurassic World Facts, the flight speed of a Pteranodon is twenty-five to thirty miles per hour. This same application describes their flight pattern as similar to the modern albatross, though P. l. masranii flies with near-constant wing strokes rather than gliding with occasional flapping. It may fly with rapid flaps at times, while using thermal updrafts from the ocean to fly slowly at other times.

Fossil pterosaurs are believed to have had coatings of pycnofibers, which are similar to feathers or hair. However, InGen’s specimens have bare, leathery skin. Some models of P. l. longiceps do depict it with a full coating of pycnofibers; this variant has never been observed directly.

Coloration among the pteranodontids is quite variable. Pteranodon longiceps longiceps has a blue-green body, countershading on the belly, and a grayish beak and dark blue-green crest. Its wing membranes have lighter color. Some artwork has depicted them with a red crest, blue body, white countershading, and yellowish-tan wing membranes. The junior novel Survivor describes one with red and gold wing markings, similar to those seen in P. l. masranii.

Female Pteranodon longiceps hippocratesi are generally tan or pink in color, though the dorsal side is patterned black or gray. The face has elaborate patterning with yellows, tans, pinks, and grays decorating the head and beak, while the crest is colored similarly; the eyes have dark orange sclerae and round black pupils. The area around its eyes, as well as its throat, are red or pink. Its wings are generally lighter in color than the dorsal side of its body, and often have dark mottling toward the tips. A darker-colored individual, presumed to be a male, has been depicted in a number of sources; it is mostly gray, with white or very light gray markings near the wingtips. The neck has whitish speckling and the crest becomes bright red toward its tip, but it lacks other significant coloring. The junior novel Flyers describes a senescent male P. l. hippocratesi with plain brown colors and a sexually-mature adult with crimson markings, a sexually mature female with blue and gray markings, and four subadult males; one of these has gold-tinged wings, another has silver streaks on the wings, a third has red wings, and the final one has blue and red spots on its wings.

Pteranodon longiceps masranii has a more subdued, grayish body color in most individuals, though some have reddish, bluish, purplish, or brown shading. The undersides of the wing membranes are yellow- or red-orange, with some black or gray streaking, and the face and crest have a tough mask-like covering which may be light to dark red, cyan, or violet. The red color appears to be most common. Some individuals have a similar color down the spine, while others have white or pale yellow stripes on the wings.

Growth

Juveniles of P. l. hippocratesi have been observed. They have a color pattern similar to the adult females, but less elaborate and lighter-toned. Young juveniles, often called “flaplings,” are capable of flight already despite not being as powerful as adults. Upon hatching, the wings are actually fully developed; while they are within the egg, the wings are tightly folded. The crests are very small at this stage, and grow out as the animals mature. The head is proportionally larger, and the eyes are considerably larger in proportion to the head. At the stage at which the flaplings were observed in 2001, they had wingspans of approximately nine feet and body lengths of three feet and two inches.

Flapling P. l. longiceps can be hatched in the mobile game Jurassic Park: Builder, which similarly depicts them as having smaller crests and larger heads than the adults. Finally, the flapling stage of P. l. masranii is a part of Jurassic World: The Movie Exhibition, also demonstrating a smaller crest but overall larger skull size in relation to the body. The beak is proportionally shorter than that of the adult, a feature not seen in the other subspecies.

The natural growth rate is unknown, but a female P. l. masranii hatched in 2011 or 2012 was fully mature by 2018. This would mean it matures in six or seven years. In the junior novel Flyers, four juvenile male P. l. hippocratesi were strong enough to fly long distances and hunt for themselves and were large enough to be a threat to humans despite being, at most, around a year old.

Sexual Dimorphism

Considerable confusion exists as to the sexual dimorphism in all of these animals. In fossil specimens of Pteranodon longiceps, females are considerably smaller than males, with an average wingspan of twelve feet (compared to the average male’s eighteen-foot wingspan, while exceptional individuals reached around twenty feet). In addition, the crests of females in the fossil record are short, small, and rounded, while males have longer crests. Males can be identified by their narrow hips, while females have wide hips with large pubic openings in order to lay eggs.

For a time, there was some speculation that InGen’s Geosternbergia was the male form of Pteranodon longiceps longiceps, while all of the P. l. longiceps were the females of this single species. This has not been confirmed as fact. All individuals of these two taxa that have been observed so far resemble males of their respective genera, but their actual sexes have not been confirmed. Canon consultants have since treated Geosternbergia as separate from Pteranodon, suggesting that InGen did create both genera separately and that they are not intended to represent sexual dimorphism within a single species. However, some concept art does indicate that the females of both would have been duller in coloration.

Pteranodon longiceps hippocratesi females can achieve thirty-two-foot wingspans and possess the long crests of males, though adult males have never been observed directly. A model of a dark-colored, red-crested individual of this subspecies exists, and is generally assumed to represent the male. In the Jurassic Park /// arcade game and in Jurassic Park /// Builder, the dark-colored presumed male is depicted as being significantly larger than the females with a 14-meter (49.5-foot) wingspan, but the junior novel Flyers depicts them as being roughly the same size. Aside from coloration and maximum hypothetical size, there do not appear to be any differences between the sexes.

Only females of Pteranodon longiceps masranii have ever been observed up close. They have very short and small, but triangular, crests; however, they have 18-foot wingspans, making them as large as the average adult male in the fossil record. What appears to be a male version of P. l. masranii appears in the mobile game Jurassic World: The Game, though the Code 19 dialogue still refers to it as a female; it possesses the longer crest of the male. In-game factoids describe it as having a 26- to 33-foot wingspan, while the Jurassic World website gives 18 feet as its wingspan. This would mean that males are between 31% and 45% larger than females, compared to the fossil record’s range of males being 33% to 41% larger than females. If correct, this would mean that Pteranodon longiceps masranii is more or less comparable to fossil P. longiceps in terms of sexual dimorphism, the main exception being its significantly larger size.

Male Pteranodons, assumed to be P. l. masranii, appear in the background in the motion comic episode “Dinosaur Crossing,” but not in significant detail. The stylization of the comic means that its depictions may be unreliable.

Habitat

Preferred Habitat

Pteranodon is a marine species, living on coastlines. In prehistory, they inhabited the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow warm-water ocean which separated North America into two subcontinents during the Cretaceous period.

Their preferred habitats are rocky islands and cliffs near the ocean, where they can remain safe from terrestrial predators and search for fish and other prey. They may shelter in caves or crevices among hills and mountains. Forest environments are also suitable since they provide food and shelter, though they need open space in which to fly. Pteranodon appears establish huge ranges; Jurassic World researchers estimate that they would form territories spanning a radius of 120 miles or more. Their habitat must consist of more than 430,000 square feet and contain a large, deep body of water. However, they may venture into desert and grassland environments where larger water sources are rare; when they do so, they are likely to gravitate toward freshwater lakes or artificial sources of water.

When released from captivity, Pteranodons have almost exclusively been seen to migrate northward away from the equator, which some behaviorists suggest is due to genetic memory. Their range includes strongly seasonal environments as well as temperature extremes. This makes Pteranodon a highly adaptable creature, capable of surviving in the humid tropics as well as arid deserts and the cooler climates of the Pacific Northwest. In the Nevada desert, temperatures during the daytime in July can reach up to 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43.3 degrees Celsius) and during the night drop as low as 40 degrees Fahrenheit (4.4 degrees Celsius). Such a rapid and extreme temperature change is difficult for many species to adapt to, but a small group of P. l. masranii were sighted in Las Vegas, Nevada during July and therefore are known to be able to tolerate these drastically changing temperatures without noticeable difficulty.

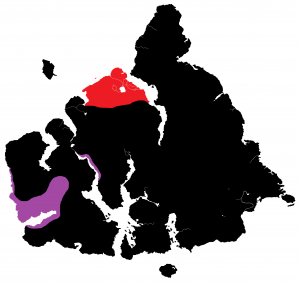

Muertes Archipelago

Pteranodon longiceps longiceps and Pteranodon longiceps hippocratesi were cloned by InGen between 1986 and 1993. At least three P. l. hippocratesi were fully mature by June 12, 1993 and may have been present on Isla Nublar, so it is likely that they were cloned some years prior to this. An aviary was constructed on Isla Sorna to contain the P. l. hippocratesi, but the containment measures for the other pterosaurs is currently unknown. The existence of other aviary structures on the island is currently unconfirmed. As of InGen’s last count in 1993, there were ten Pteranodons living on the island; how many were actually Geosternbergia is not known, or if any Geosternbergia remained by 1993. Including both P. l. longiceps and P. l. hippocratesi, there were precisely ten adult Pteranodons encountered between 1997 and 2001, though the P. l. hippocratesi are said to have been a covert project according to film director Joe Johnston and thus may not have factored into InGen’s overall headcount.

By 1997, the pterosaurs with the exception of P. l. hippocratesi had broken free of whatever containment measures were in place on Isla Sorna. Six adult P. l. longiceps were sighted in the island’s northern grasslands on May 25; they are presumed to be males due to their crest morphology, but this is not confirmed for certain. Older concepts for The Lost World: Jurassic Park would have depicted either Pteranodon or Geosternbergia living within and near the Workers’ Village. Several may have lived off of the island’s southwestern shore according to older Jurassic Park /// scripts, which indicate that these pterosaurs were responsible for the deaths of Enrique Cardoso and his associate. The junior novel Survivor depicts at least two Pteranodons, one living on the sandy western coast of Isla Sorna (which may have been killed by a Tyrannosaurus) and another circling near the Embryonics, Administration, and Laboratories Compound. The first sighting was on May 23, while the second sighting was on May 27. Several days later, a Pteranodon was sighted in the southwestern part of the island over a dry and deforested valley; Eric speculated that it might have been the same individual he saw on May 23, suggesting that it was colored similarly. The next junior novel in the series, Prey, depicts one adult Pteranodon roosting on Mount Hood on the night of December 30 and one flying near the Jurassic Park Ranger Station on the morning of December 31.

The range of Pteranodon longiceps hippocratesi was much more restricted. Unlike the other pterosaurs, they failed to escape containment on their own. However, they did successfully breed, which implies that at least one male existed in the aviary at some fairly recent point. On July 19, 2001, there were four adult females and six flaplings in the aviary. An incident occurring that day resulted in the death of one of the adults and possibly one of the flaplings; the surviving three adults were unintentionally released and left Isla Sorna.

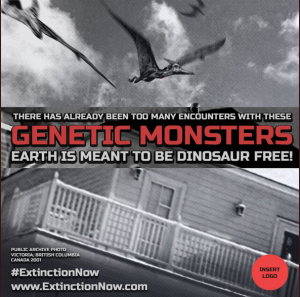

According to the junior novel Flyers, the third in the series, a family of escaped Pteranodons were eventually returned to the aviary on Isla Sorna in July of 2002. The novelization implies that they are the individuals released on July 19, but the descriptions do not match up, and later material confirmed that those particular animals were neutralized in Victoria, British Columbia. Additionally, the novelization makes mention of several other adult males in the aviary which do not appear. It has been speculated since the release of Jurassic Park: The Game that these inconsistencies could be cleared up by explaining the pterosaurs from Flyers as the escapees from the Jurassic Park Aviary, but as Universal Studios has not confirmed the second two Jurassic Park Adventures junior novels or the existence of the game’s Pteranodons as part of the official film canon, there is no evidence for the hypothesis. Nonetheless, The Evolution of Claire officially confirms that escaped Pteranodons were, in general, recaptured and held on Isla Sorna.

Between late 2004 and May 2005, the remaining Pteranodons from Isla Sorna were rounded up and transported to Isla Nublar by Masrani Global Corporation. Supposedly, none remain on Isla Sorna, though there is mounting evidence that InGen and other interested parties are covering up continued activity there. Other islands in the Muertes Archipelago may house surviving pterosaur populations, but since the islands are under strict watch and access is prohibited, this cannot be investigated.

Isla Nublar

An aviary was constructed in Jurassic Park on Isla Nublar to contain Pteranodons. However, no DNA from this species was maintained on-site, and the animal itself would likely not be put on display until Phase II of the Park’s operation. This aviary was situated on the Jungle River and was bordered to the east by the Stegosaurus paddock. The main tour road, as well as the Jungle River Cruise and one service road, would have crossed through the aviary. To the north and south, the aviary would have bordered undeveloped land, while to the west it would have bordered some undeveloped land and the southeasternmost corner of the Proceratosaurus paddock.

It is unknown how many Pteranodons were present on Isla Nublar as of June 11, 1993. However, based on Jurassic Park: The Game, there were at least three or four Pteranodon longiceps hippocratesi on the island at the time of the incident, which escaped confinement and traveled northward and eastward across Isla Nublar before disappearing. Three were sighted near the eastern mountain range on June 12, and one was sighted north of the Visitors’ Centre near the Western Ridge later that evening. Their location after the incident is unknown.

In 2004, a new aviary was constructed on Isla Nublar near the northern end of the Jungle River to house the Pteranodons. Originally the structure was going to be made of glass, but the pterosaurs were able to break the glass using their beaks and escape. This necessitated the development of a new transparent polymer to use instead. As of August 2004, there were no pterosaurs on Isla Nublar; however, InGen geneticist Dr. Henry Wu had created the first embryos of Pteranodon longiceps masranii by that time, and twelve eggs were incubating. These included one individual (Egg B) exhibiting polydactyly on one wing, meaning it bore an extra finger. According to Dr. Wu, the incubation period lasts for several months; it is not currently known when the first P. l. masranii hatched.

Between late 2004 and Jurassic World‘s opening date of May 30, 2005, the remaining Pteranodons were removed from Isla Sorna and transported to the Jurassic World Aviary. These would have included any remaining P. l. longiceps and P. l. hippocratesi, though it is not known how many of each remained by that time. Additionally, P. l. masranii would have been introduced to the Aviary as they matured. There do not appear to have been any further attempts to breed the other subspecies. By the end of 2015, the sole remaining pteranodontid on Isla Nublar appears to have been P. l. masranii.

A female Pteranodon longiceps masranii is confirmed by the Dinosaur Protection Group to have hatched in Jurassic World sometime between May 15, 2011 and May 17, 2012. This individual was said to still be alive as of May 15, 2018 and was a six-year-old adult at that time.

On December 22, 2015, an incident involving the hybrid Indominus rex caused a breach in the Aviary; this permitted the pterosaurs to escape. Upon being released, they initially flocked westward over the forests, but turned south somewhere near the ruins of the old Visitors’ Centre. From here, they flocked toward the largest nearby body of water, the Jurassic World Lagoon. At least 44 adult females were involved in this. The ensuing incident left several Pteranodons deceased; some were shot in defense of JW001 and Simon Masrani, and many were tranquilized in midair by the Asset Containment Unit; some of these either fell from such a height as to sustain fatal injuries or fell into the Lagoon where they likely drowned. One was consumed by the Mosasaurus which inhabited the Lagoon. At least eleven of these animals died during the incident. During the night, by the time Sector 3 had been largely abandoned, the animals began to return; some of them followed the monorails as they continued along their automated paths. At least two monorail trams were destroyed by the Pteranodons; during the second such incident, one animal was struck by a monorail, but it is not confirmed whether it died. It is similarly uncertain whether any died in explosions that occurred when the monorails were destroyed.

Once the island was largely abandoned, the Pteranodons settled and began finding new homes. At least five were confirmed in Gyrosphere Valley as early as December 23, while a few others stayed near the Lagoon; however, since this was not a safe fishing hole due to the mosasaur, not many seem to have fed here. According to the Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom LEGO website, some of the Pteranodons remained near the Lagoon, roosting in the abandoned hotel complex. Others nested on the island’s coastal cliffs, as the ocean was a far safer place to feed than the Lagoon. Their most prominent nesting site was the Eastern Ridge, where they were confirmed roosting by December 24.

In June 2016, the mosasaur was accidentally released into the ocean and migrated westward, but the pterosaurs do not appear to have returned to the Lagoon in large numbers, since none were sighted there in 2018. As of June 2016 their roosting grounds appear to have been concentrated in the areas bordering the central valley.

At least four adults were seen near Isla Nublar’s southern coast on February 17, 2018; they had longer crests than an average female, but their sex is unconfirmed. They possessed a combination of features of different subspecies; their long and sharp beaks resemble those of P. l. masranii, but they possess teeth like P. l. hippocratesi. This implies that they may be crossbreeds of these two subspecies. If true, they can be differentiated from full-blooded P. l. hippocratesi by the larger size, but smaller number, of their teeth as well as the sharp beak tip.

A photograph procured by the Dinosaur Protection Group and featured in a June 5, 2018 article by Klayton S. confirms the continued presence of P. l. masranii on the island. At least twenty-eight adults or subadults can be seen in the photograph. All of these appear to be female. The location at which the photograph was taken is unknown, but appears to be on one of Isla Nublar’s mountains, probably within the Eastern Ridge as they were known to nest here.

They appear to gradually have migrated north, and on June 23, 2018 they were sighted almost exclusively within the vicinity of Mount Sibo. A flock of at least thirty-five females was seen fleeing from a volcanic disturbance at around midday, and a similarly-sized flock of females could be seen fleeing the island during the most violent part of the volcano’s eruption. At least one was killed during the eruption due to being struck by volcanic debris, while three others were removed from the island via the S.S. Arcadia by the mercenary team led by Ken Wheatley at the behest of Eli Mills.

The 2018 population size can be used to estimate the 2015 population. At least 35 individuals were seen west of Mount Sibo, and at least 35 were later seen east of Mount Sibo. These two flocks may have been the same group of animals, but if they were two different flocks, there would have been at least 70 animals on the island at that time. Additionally, three were already caged on the Arcadia, plus at least 11 which died during the 2015 incident. This means that there were at least between 49 and 84 Pteranodon longiceps masranii in the Jurassic World Aviary before the incident.

After the eruption of Mount Sibo, it is likely that many of the Pteranodons fled the island. Some, however, were seen perching on coastal rocks while the eruption continued, and as their diet of fish would have been uninterrupted by the volcano’s activity, it is not impossible for a decent number to have remained on Isla Nublar’s coastal cliffs even after the eruption occurred.

Mantah Corp Island

Eight adult female P. l. masranii, possibly captured after escaping from Jurassic World, were obtained by Mantah Corporation in June 2016. They were contained without the knowledge of any outside party, as the company had been illegally acquiring specimens from InGen for some years. These animals were housed in a clandestine testing facilitly on Mantah Corp Island.

The Pteranodons in particular were introduced to the redwood forest biome. One of them collided with the habitat’s geodesic dome, which is paneled with LCD screens, shortly after its release. It may have died due to injuries sustained.

BioSyn Genetics Sanctuary

After many species of de-extinct animal were released into the wild in 2018, some of them began causing problems, particularly aggressive species like Pteranodon. To deal with them, BioSyn Genetics was authorized by several governments to capture and contain these animals at specialized facilities. The biggest of these was the BioSyn Genetics Sanctuary, located at the company’s headquarters in BioSyn Valley of the Italian Dolomites. This facility, which operated in the early 2020s, housed Pteranodon longiceps masranii specimens. The facility’s Aerial Deterrent System forced airborne life such as Pteranodon to remain within 500 feet of the valley floor; only when these safeguards were deactivated could the pterosaurs rise higher.

In early 2022, a wildfire led to an emergency evacuation of the valley. The Pteranodons and other animals were herded into emergency containment whild the fire burned, and were reintroduced after the valley was deemed safe again. After this incident, which also exposed systemic corruption in BioSyn, the United Nations began directly overseeing the facility.

Black market

Mercenaries led by Ken Wheatley retrieved at least three adult female Pteranodon longiceps masranii from Isla Nublar shortly before the eruption of Mount Sibo on June 23, 2018. They were removed from the island via the S.S. Arcadia and transported to the Lockwood Estate near Orick, California where they remained during the night of June 24. They were released from captivity by Maisie Lockwood to save them from hydrogen cyanide poisoning, upon which they fled into the surrounding pine forest.

Since then, these animals have become relatively easy to locate, making them ideal candidates for the black-market trade. Their aggression makes them appeal to less than savory individuals. Live specimens and DNA can be obtained illegally at presumably steep prices, and anyone with enough technological and financial means should now be able to clone Pteranodons of their own. The Amber Clave night market, a globally-known black market for de-extinction technology and specimens, probably sees quite a bit of Pteranodon material pass through its hidden Maltese stalls.

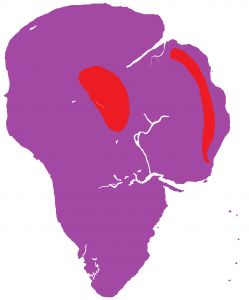

Wild populations

Pteranodon first evolved about 86 million years ago in North America; fossil remains have been found in marine deposits from the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow sea that divided the continent in the Cretaceous. Remains are more common in what was then Laramidia, the western subcontinent, but this is due to geology; it is likely that the pterosaurs lived in Appalachia to the east as well, but fossils here are simply less common. These were highly successful pterosaurs, being important members of the marine ecosystem in North America. Later in the Cretaceous period, they began to die out as their environment changed, not the least of which was the loss of the seaway due to dropping sea levels. Around 84 million years ago, Pteranodon became extinct. These animals were cloned using genetic modification during the late twentieth century, restoring them to life (albeit with genetic alterations).

Because of their strong flight capabilities, Pteranodons have left the islands in the Gulf of Fernandez where they were bred on numerous occasions. Three adult female P. l. hippocratesi which were released from the Site B Aviary on July 19, 2001 were eventually sighted over Victoria, British Columbia later that year. American security contractor Vic Hoskins apprehended and neutralized them in the woodlands near Vancouver a few miles away.

A different fate is given for the escapees in the junior novel series Jurassic Park Adventures; they are mentioned in Prey and physically appear in Flyers, by which point the flock consists of an old male, a mated pair including the elder’s daughter, and four sons belonging to the mated pair. The pterosaurs travel the subtropics around the world, with confirmed sightings and attacks in South America, Mexico, Texas, and the Florida Keys. Unconfirmed rumors had placed the pterosaurs in farther parts of the world, such as Britain and Japan. In July of 2002, the family had reached Florida and flocked to Universal Studios at Orlando due to the large artificial pool in the center. A tense day-long standoff between the pterosaurs and parkgoers ends with the animals being led to Isla Sorna and housed in the aviary. As discussed above, the idea that these are the Isla Sorna Pteranodons contradicts several aspects of the film canon, and it has been hypothesized that they could actually be the Isla Nublar Pteranodons from Jurassic Park: The Game, whose existence is also questionable.

After the 2015 incident on Isla Nublar, the Pteranodons were able to freely move about the area surrounding the island. Jurassic World’s official website states that the natural range of their pterosaurs would cover over 120 miles, which would allow them to comfortably fly between Isla Nublar and western Costa Rica. However, none were reported off-island until several years later. On June 24, 2018, three captured Pteranodons were released into the wild near Orick, California. Shortly after, three adult female Pteranodons were seen flying north along the Northern California coast; these were presumably the same three that were released previously. At least two adult male and two adult female Pteranodons were seen flanking a passenger aircraft in June or July 2018. These were among the few males known at the time, and likey descended from Isla Sorna populations.

Also in July 2018, three adult female P. l. masranii were sighted at the Vegas Strip in Las Vegas, Nevada. This would place them roughly 150 miles from the nearest ocean. The animals most likely followed the Colorado River north from its estuary in the Gulf of California, searching for sources of water. Pteranodons were sighted diving into Lake Mead earlier in the same week as the Vegas incident, suggesting that they had migrated northeast in search of food and water in the desert. The city has since become an oasis for the animals, which are frequently seen there. Graffiti found near Las Vegas even today suggests the area to be a common territory for these reptiles; locals are no longer comfortable walking outside on the Vegas Strip and caution visitors to pass on through without stopping.

North America is known to host several large flocks of Pteranodons today, some of which are transient and migratory while others set up permanent residence in ideal habitats. They are most commonly sighted in western North America, especially the U.S. states of Oregon, Nevada, Arizona, Texas, Oklahoma, Minnesota, and Illinois. Migrating flocks became a common sight by 2019, including a publicized incident in which a subadult female was filmed by wedding guests in Pinewood, Minnesota preying on a dove released during the ceremony. By the spring and summer of 2022, these flocks had increased both in size and number. A large flock was confirmed nesting on Mount Fromme in Vancouver, British Columbia; this flock includes at least nineteen adults. It nests fairly close to where the 2001 escapees were captured, suggesting this is an ideal habitat for the pterosaurs. Another resident flock exists in Nashville, Tennessee; this flock became famous in June 2022 when rock singer Chris Daughtry was allowed by his publicity team to release footage from earlier in the year in which he was dive-bombed by a female Pteranodon in Bicentennial Park. Males are also known in North America, despite no male Pteranodons being a part of the original Jurassic World population. A pair of males were photographed in 2022 near Helena, Montana in Lewis and Clark National Forest. Most of the present-day population are P. l. masranii, the Jurassic World subspecies, but the others have been confirmed in more recent times. Their flocks range all across the continent, from northern Alaska, the Canadian Archipelago, and Greenland all throughout the continental United States.

South America also has its own Pteranodon populations. On May 14, 2022, a civilian reported three females to the Department of Prehistoric Wildlife from Chilca, Peru. Others have been tracked by the CIA along the Atlantic coast of Brazil and in southern Patagonia.

The first Pteranodons confirmed in Europe were a pair of females which were sighted in Málaga, Spain on November 12, 2021. These two likely crossed the Atlantic Ocean from North America, and temporarily roosted in the city. During their stay, one of them damaged a security camera on a government building. Others sighted in Europe, tracked since at least 2021 by the CIA’s dinosaur tracking division, are known to live in Sweden, Iceland, and Poland.

Other Pteranodons crossing the Atlantic have reached Africa, being sighted mainly on the northwestern coasts. Four of them were sighted by tourists in the Canary Islands, photographed from an airplane flying over the island of Montaña Clara. This uninhabited island is a prime habitat for seabirds and now appears to host a Pteranodon population, being an ideal nesting ground for these pterosaurs as well. They venture as far inland as the Algerian Sahara, though they are more common farther south in countries including Nigeria, Angola, and Tanzania.

Pteranodons have been sighted in southern and eastern Asia as well. A migratory flock of nine adults was photographed in the spring of 2022 over Chandni Chowk, India, while a residential flock is known to nest near Lake Ashi in Hakone, Japan. Summer came with the first sighting from South Korea, in the city of Seoul. These Pteranodons likely dispersed from Central America and western North America across the Pacific Ocean. The CIA has tracked other populations throughout most of Russia, including the remote Siberian Arctic, where they hunt from the many rivers in the region. Others inhabit China, particularly the river systems in the east, as well as Afghanistan and Turkmenistan.

Some of the Pteranodons which dispersed across the Pacific have remained there, using the bountiful waters of this ocean as a source of food. They are common throughout Indonesia, and are known to nest in eastern Australia. Pteranodon also holds the distinction of being the first de-extinct animal reported in Antarctica, where it nests and feeds all across the coasts of the Southern Ocean. This makes Pteranodon the most widely-distributed of all de-extinct animals, found on every continent and in every ocean.

Behavior and Ecology

Activity Patterns

Pteranodons are cathemeral, active at some times during the day but resting at other times. They appear to sleep at night, but are shown to become active at night if disturbed in the junior novel Prey as well as deleted concepts for The Lost World: Jurassic Park. In both cases, the animals were portrayed becoming aggressive toward the people who had disturbed them. Sometimes, P. l. masranii has been observed active at night, typically in areas where human activity alters their behavior patterns; they are particularly easily disturbed by noise, light, and visible moving objects.

The junior novel Flyers, on the other hand, portrays a family of P. l. hippocratesi adopting a nocturnal lifestyle in order to avoid human activity, a behavior that has been observed in numerous mammals in real life. However, they still hunt during the day, though they prefer to actually feed on their captured prey in the evening or at night.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

These reptiles are considered to be piscivores, meaning that their diet consists largely of fish. Still, this animal does actually feed on other prey fairly often. It has been observed targeting humans and small dinosaurs for food, and likely preys on many types of small animal. When permitted to live in the wild, it will usually hunt fish in the ocean; however, it has done well in captivity on a diet of brackish-water or freshwater fish and other small animals. When hunting small prey, the sharp and pointed beak is used as the primary weapon, stabbing or scratching at the prey item. Biting at prey is most effective in Pteranodon longiceps hippocratesi due to its teeth, which are absent in all other forms of pteranodontid. Often, these pterosaurs will soar high above the ground riding warm updrafts while scanning the area below for food. Both P. l. hippocratesi and P. l. masranii are known to feed on birds by diving at them while in flight and rapidly grabbing them with their beaks.

Due to genetic modification, InGen’s Pteranodons have grasping feet similar to those of birds of prey. While fossil specimens would only be able to use their feet to walk, InGen’s have adapted to their altered anatomy in several ways, most prominently by using their feet as hunting implements. A Pteranodon will grasp the upper body of a potential prey item and lift it into the air, dropping it into an ideal feeding location. However, this is not always a viable way to capture prey. An adult female Pteranodon longiceps hippocratesi struggles to hold an adult human aloft, though it can carry a child without much difficulty. On the other hand, an adult female Pteranodon longiceps masranii can easily lift an adult human into the air with no trouble at all; they have even been observed trying to pick up juvenile Triceratops, which can weigh around five hundred pounds, but can only hold them above the ground for a few seconds before dropping them. If a Pteranodon drops its prey from a great enough height, or onto dangerous terrain, it may easily injure its prey.

Additionally, Pteranodons can take advantage of water to collect prey. In the junior novel Flyers, as well as during the 2015 Isla Nublar incident, Pteranodons were observed picking up humans and dropping them into large bodies of water where they would feed on them later. This was shown to be highly organized in Flyers, due to the dramatically increased intelligence of the P. l. hippocratesi and their strong familial relationships. Collected food would be eaten later, when the strongest male of the group permitted the family to feed. This cacheing method was less organized with the P. l. masranii on Isla Nublar, which only successfully captured one human this way, and continuously squabbled over their prey. However, unlike P. l. hippocratesi, which does not appear able to swim, P. l. masranii is an adept diver and can swim under the surface of the water. It may plunge into water from a great height by folding up its wings and essentially turning its body into a giant dart. Fossil evidence suggests that they could also float on water similarly to seabirds, plucking prey from beneath.

A feeding behavior only observed in Pteranodon longiceps masranii involves a “feeding frenzy” method in which a large number of pterosaurs generates panic in their prey by swooping and vocalizing loudly. This initiates a fight-or-flight response in prey items, which may then act illogically while attempting to escape. While the prey items are panicked, the Pteranodons may easily pick off stragglers or injured animals. They have been observed associating with the smaller Dimorphodon in such feeding frenzies. Despite the apparent group effort of these hunts, there is no actual cooperation among the animals; they are known to fight over food and do not assist one another in any intentional way.

Other methods of subduing prey used by Pteranodon include plowing into prey feet-first with wings outspread to knock over multiple victims, landing on top of a prey item and repeatedly bashing it into a hard surface, and making hit-and-run strikes with their talons while airborne. They may also scavenge carrion; a model produced for Jurassic Park /// portrays P. longiceps hippocratesi perching on a rocky structure with the carcass of an infant male Tyrannosaurus rex nearby.

Pteranodon dung is distinctively birdlike, being gray or whitish and caking onto surfaces. When wet, it is foam-like; when dry, it crumbles easily. Its appearance and texture are similar to that of other piscivorous animals.

Social Behavior

Pteranodons are highly gregarious animals, nearly always seen among members of their own kind. Pteranodons are frequently seen in groups of three; however, they have also been sighted solitarily from time to time. Depending on the availability of food and water sources, flocks of Pteranodon adopt either migratory or resident behaviors; migratory flocks travel around from one nesting site to another, while residential flocks remain in place year-round.

Due to its population size, the largest flocks of Pteranodon were those of the P. l. masranii on Isla Nublar. Flocks of these pterosaurs may contain thirty to forty animals. Since the eruption of Mount Sibo disturbed their nesting ground on the volcano’s slopes, their flocks scattered and have taken time to recover. Groups of one to four have been sighted commonly since 2018, with groups of between ten and twenty becoming common in 2022.

When socializing with one another, Pteranodons tend to be quite loud. However, not all of their social displays involve vocalization. The head crests are presumed to be display structures, and the variability of facial and crest color in P. l. masranii in particular implies that they engage in visual displays. The bright red crest of the black P. l. hippocratesi also suggests a display purpose, and if this is the male of the subspecies, it is likely used for courtship or to intimidate rivals.

According to the account in Flyers, familial bonds among Pteranodon longiceps hippocratesi can be extremely strong. In this account, a family group consisting of a senescent male, his daughter, her mate, and their four sons settled in Orlando, Florida after being attracted to a large artificial pool in the Universal Studios theme park during a drought. The eldest male, grandfather to the four young males, acted as a kind of mentor figure to the younger animals. In animals with strong family ties, the role of mentor is often taken up by animals that have passed reproductive age. The sexually-mature male was in charge of coordinating the hunting efforts and was high in the family’s pecking order; however, he would not start feeding until all his family was present and safe, indicating a level of empathy that likely resulted from the unusually increased intelligence of P. l. hippocratesi demonstrated throughout this account. The entire family group delayed their migration through the area due to their second-youngest flock member becoming injured; they refused to abandon one of their offspring even when there was no chance of his recovery without human intervention.

A deleted concept for Jurassic World also demonstrates a similar empathic tendency in Pteranodon longiceps masranii, despite that subspecies’s lesser intelligence and tendency toward squabbling. In this scene, one of the Pteranodons would have been seized by the Mosasaurus while attempting to extract a human from a damaged monorail over the Jurassic World Lagoon. Several other Pteranodons would have rushed to its aid, pecking at the mosasaur and risking their own safety in an attempt to rescue one of their flock.

Reproduction

Pteranodon lay eggs in the manner common to pterosaurs, roosting in safe areas where predators cannot reach, such as cliffs, rocky pinnacles, and tall buildings; it nearly always nests near a source of food and water. At least P. l. masranii may decorate its nests with attractive items it finds, since some have been seen collecting small shiny objects. Even non-reproductive Pteranodons will build nests to live in; the eggs are probably laid in preexisting nests.

According to Flyers, the males of at least Pteranodon longiceps hippocratesi will engage in physical combat in order to win the rights to mate; their efforts may be judged not only by the females, but by the females’ male relatives. In this subspecies, pair-bonds are very strong and may persist for years, if not a lifetime.

The eggs are bright white, roughly three times the size of a chicken‘s egg; unlike the eggs of dinosaurs, pterosaur eggs have softer and more permeable shells with a texture like parchment. This means they are more vulnerable to the elements, like those of most modern reptiles, and must stay sheltered for their protection. Twelve eggs from surrogate parents were incubated simultaneously to hatch the first-ever Pteranodon longiceps masranii. Which subspecies was used to obtain the surrogate eggs is currently unknown. Similarly, a nesting colony of either P. l. longiceps or Geosternbergia was planned to appear in The Lost World: Jurassic Park and would have contained twelve eggs (some of which would be unintentionally destroyed by a helicopter, prompting the parents to attack). The Pteranodon longiceps hippocratesi living in the Site B Aviary as of the summer of 2001 were observed to have six living offspring, while the breeding pair of the family group from Flyers had four living male offspring as of July 2002; however, the original number of eggs laid in each case is not known. Nests consist of sticks, driftwood, foliage, and other debris that the parents collect from the environment, and are typically placed on top of natural or artificial structures where predators cannot easily reach.

After an incubation period of several months, the eggs will hatch; the young are sometimes called “flaplings” at this stage because they are capable of limited flight fairly quickly. Young flaplings are already tenacious predators, eagerly pursuing prey and taking it down using methods similar to the adults. In P. l. hippocratesi, adults may actively teach their young how to hunt. One individual (presumed to be the mother) will often deliver live food to give the flaplings the opportunity to hunt and kill live prey, helping them develop essential survival skills for later in life. While other adults will cooperatively protect the nesting territory, only the parent appears to provide direct care to its own offspring. The account in Flyers depicts a multigenerational group of P. l. hippocratesi maintaining very strong familial bonds between animals of three successive generations, even after the youngest had become capable of defending themselves. This behavior is unconfirmed in the less intelligent subspecies.

During the 2001 Isla Sorna incident, the pterosaur that was presumed to be the mother of six flaplings died due to the collapse of abandoned aviary infrastructure. Following her death, the other adults abandoned the offspring to fend for themselves, seeking out new nesting grounds on the North American mainland. While it is unusual for adult animals to vacate a territory for juveniles to inherit, rather than evict the juveniles, it may be that the limited size of the aviary and competition for prey with other piscivores made this a less suitable territory. The flaplings, while capable of flight, were too young to journey with the adults and were abandoned. This confirms that, while adults will tolerate the offspring of other Pteranodons, they do not act as surrogate parents. Adoptive behaviors like those seen in many dinosaurs are not known in pterosaurs at all, which may be due to the precocious nature of pterosaur young. Parents provide care for their own offspring, but not to juveniles with no genetic relation.

Communication

The sounds produced by Pteranodon are highly varied. Screeching, squawking, and cawing noises are often used to communicate with one another while flying, with different calls used while traveling or hunting. These sounds are probably used to relay information throughout the flock, and to coordinate their movements as to avoid midair collisions. Even lone Pteranodons can be heard making such vocalizations, suggesting that they serve purposes beyond intraspecies communication. The coloration of the body is variable enough to suggest that it helps the animals identify one another, and the crest is believed to serve as a visual signal as well. The junior novel Flyers details the ways that Pteranodon longiceps hippocratesi visually identify one another using body coloration, as well as their specific social, aggressive, and distress calls.

Cawing sounds are often used to signify aggression, and may be used during hunts to startle prey into moving. Growls and hisses are also used when confronting threats, in addition to loud shrieks which are used to intimidate enemies or alert other Pteranodons to danger.

Ecological Interactions

A primarily coastal-dwelling species, the Pteranodon feeds on fish that venture into shallow water, such as possibly bonitos. As they sometimes hunt on tidal rivers or bodies of freshwater, they could potentially come into conflict with spinosaurs; at least one has been witnessed competing for prey with a Velociraptor antirrhopus masranii. Prey other than fish are confirmed to include humans, which Pteranodons hunt with surprising frequency. They have been witnessed on occasion attempting to prey on juvenile Triceratops and Ankylosaurus, and chasing after Franklin’s gulls (Leucophaeus pipixcan). Since their introduction to North America, they have been observed feeding on domestic pigeons (Columba liva domestica).

Because of their wide-ranging habitat, Pteranodons share territory with numerous other animals. As they are rather aggressive toward other species and highly territorial, they likely come into conflict with rival species fairly often. On Isla Nublar, they have been sighted in areas that were home to carnivorous dinosaurs such as Teratophoneus, Carnotaurus, Ceratosaurus, Allosaurus, and the fish-eating Baryonyx and Suchomimus, with which they likely competed for prey. Many species of herbivorous dinosaurs also live in their territory, as do the omnivorous Gallimimus and diminutive Compsognathus, which have unknown relationships to Pteranodon; it may have preyed on the smaller dinosaurs in its environment such as compies and Microceratus. Juveniles of many dinosaurs may have been food items; it has been seen near populations of Sinoceratops, Stegosaurus, Peloroplites, Ouranosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Apatosaurus, Stygimoloch, and Pachycephalosaurus, as well as possibly Pachyrhinosaurus.

On Isla Sorna, it was known to live close to animals such as Stegosaurus and Tyrannosaurus, which it does not appear to fear. This is despite two known attempts by Tyrannosaurus throughout the Jurassic Park Adventures junior novels to prey on Pteranodon; in one case, the Pteranodon had been intentionally harassing a tyrannosaur on a beach by diving low over its head. The tyrannosaur retaliated by snatching the pterosaur and thrashing it violently, possibly killing it. The second known interaction between the two species was a simple attempt at predation. Pteranodons on Isla Sorna also lived within the ranges of Brachiosaurus and, while confined to the aviary, Spinosaurus.

A supposed deleted scene from Jurassic Park /// would have had a violent conflict between Velociraptors and Pteranodons, but the nature of the scene is not known. However, a confirmed deleted scene from The Lost World: Jurassic Park would have featured Pteranodons and/or Geosternbergia living comfortably in Velociraptor territory and even laying eggs on top of a building within said territory. This suggests that these two types of animals can coexist without major issue, likely because they mostly hunt different prey. However, as mentioned above, a Pteranodon longiceps masranii and a Velociraptor antirrhopus masranii were in 2018 seen to compete for the same prey item, a juvenile Triceratops which had wandered away from its own kind.

Mosasaurus maximus is known to prey on Pteranodon; the artificial species of theropod Indominus rex has been observed attempting to attack Pteranodon without success. Its smaller relative, Scorpios rex, may have tried to prey on these pterosaurs in 2016; they were observed active during times of night when they would usually be asleep around the same time a Scorpios was seen in the area. Its relationship with the larger pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus is an uneasy one; while they will tolerate one another and may migrate side by side, the bigger reptile will not tolerate competition for food and may aggressively drive away the smaller Pteranodons from a food source. It does not eat them, however.

Not all of this pterosaur’s relationships with other animals are confrontational, however. Concept art implies that both Pteranodon and Geosternbergia can cohabit the same area, and Pteranodon longiceps masranii will tolerate the presence of Dimorphodon willingly. The exact nature of the relationship between Pteranodon and Dimorphodon is not fully understood, but it appears to be at least a commensal relationship, as the smaller pterosaurs benefit from the protection of the larger ones. In North America, Pteranodons are known to have a similar relationship with Canadian geese (Branta canadensis). Its aggressive territoriality may even indirectly benefit some animals. For example, the Troodon Jeanie laid her eggs in a hidden nest underneath a Pteranodon hunting ground; the pterosaurs’ aggression would keep away potential scavengers, meaning that the Pteranodons unwittingly acted as the eggs’ protectors.

It shows territorial behavior toward the huge Brachiosaurus, but is helpless to drive this sauropod away; to such a large animal, Pteranodon is a mere annoyance. In contrast, Pteranodons enjoy the company of Dreadnoughtus, which they will roost upon and stick close to even while it moves.

Cultural Significance

Symbolism

Pteranodon has long been known to the general public as one of the most famous (if not the singly most famous) variety of pterosaur. It is universally common in paleoart, both professional and amateur, with plenty of reference material available thanks to the abundance of this reptile’s fossilized remains. Other forms of media, such as films, comic books, and video games, almost always utilize Pteranodon as the go-to pterosaur. Whether it is depicted as ambient wildlife or as an aggressive killer varies based on the creator.

Many misconceptions about Pteranodon exist due to its ubiquitous presence in media. Laypeople may not know its name specifically, recognizing it only as a “pterodactyl.” While it is indeed a pterodactyloid, it is far from the only one, and the term “pterodactyl” is often incorrectly applied to all pterosaurs regardless of their classification. It should, of course, be used only for the suborder Pterodactyloidea (especially pedantic scientists will insist that it be used only as a common name for the genus Pterodactylus in particular). Another misclassification by the general public is that pterosaurs are some type of bird, or that they are dinosaurs. Although they are neither, they are within the clade Ornithodira as essentially cousins to the dinosaurs; this makes birds their closest living relatives.

In media, Pteranodon is often depicted as the ecological equivalent of a bird of prey, hunting mainly terrestrial animals which it grabs in its feet and carries to a nest. In reality it is more comparable to a gull, a bold and opportunistic creature hunting and feeding mainly in water. While InGen’s pterosaurs have been genetically modified to have birdlike grasping feet, this feature was not present in the original animal, which grabbed food in its beak instead. It usually eats its prey not far form where it catches it, rather than bringing it to a nest to feed its young; in fact the young hatch with their wings nearly fully formed and can fly and hunt at a very young age.

Along with Tylosaurus kansasensis, the U.S. state of Kansas has adopted Pteranodon longiceps as one of its two state fossils as of 2014.

Since being brought back to life, Pteranodon has presented the clearest example of a de-extinct life form that is able to advance into new regions without human assistance. It is a good long-distance flier and has dispersed itself along the North American coastline multiple times. Due to several incidents of it arriving in areas used by humans, and due to its territorial nature, it has become a symbol of the threat de-extinct animals can pose to modern ecosystems and human safety. This has made it one of the most politicized de-extinct species, as discussed below.

According to Universal Studios, Pteranodon is the pterosaur of the Libra astrological sign (September 22 – October 23).

In Captivity

The first Pteranodon to be brought back from extinction hatched sometime between 1986 and 1993, presumably at least a few years before 1993. There are two schools of thought on which Pteranodon subspecies was created first. One holds that P. l. hippocratesi was a kind of failed first attempt, with phenotypic aberrations that made it less suitable for Park exhibition. This hypothesis is slightly supported by Jurassic World: Evolution, where this subspecies is the default appearance and a phenotype resembling P. l. longiceps requires genetic modification. The other, which is presented in the junior novel Flyers, suggests that P. l. hippocratesi was modified intentionally to be smarter, stronger, and larger than a normal Pteranodon so that it could perform in shows for entertainment purposes. This second hypothesis is supported by Jurassic Park: The Game, which depicts this subspecies as being imported to Isla Nublar by 1993. Whichever the reason, P. l. hippocratesi was clearly held under much more secure conditions than P. l. longiceps.

It was intended to be displayed in Jurassic Park, where it would be visible from the main tour, the Jungle River Cruise, and the lodge within the aviary on Isla Nublar. At the moment little is known about the Jurassic Park Aviary other than it was scheduled to open for Phase II of park operations.

In late 2004, Dr. Henry Wu succeeded in producing Pteranodon longiceps masranii, which is believed to have fewer genetic anomalies than the preceeding subspecies. It was the first new breed of animal created for Jurassic World; twelve individuals were hatched. Eventually, this subspecies completely replaced those that had existed before it. For the full ten years of Jurassic World’s operation, these pterosaurs existed in the Jurassic World Aviary, where visitors could observe them from the secure walkways below as they soared about and fed on fish from the rivers. The Aviary remained a popular attraction throughout Jurassic World’s history and was frequently advertised, with the Pteranodons being prominently featured in marketing. Containing the pterosaurs had been an ordeal in the beginning; Masrani Global was not going to utilize a wire-mesh or metal fencing aviary structure, but glass proved susceptible to strikes from the pterosaurs’ beaks. The aviary on Isla Nublar was built from a transparent polymer which was developed specifically to withstand the pinpoint strikes of Pteranodon beaks. Another successful attempt at containment was made in 2016 by Mantah Corporation using a heavy-duty biodome with holographic LCD panels on its interior, which were used to display hyperrealistic images of the biome type in order to emulate wild conditions. Unfortunately this was not entirely suitable for the pterosaurs, as the lifelike backdrop of the holographic screens was convincing enough that the animals would sometimes collide with it in mid-flight and injure themselves.

The needs of this pterosaur in captivity are extreme and hard to satisfy. While not as intelligent as some theropod dinosaurs, it still has very high stimulation needs and will quickly start exhibiting maladaptive behaviors if it becomes bored or stressed. These include increased aggression levels, making it dangerous for its handlers. In the wild, its gets the stimulation it needs from hunting, including diving into lakes or the ocean to chase fish. To keep it satisfied in captivity, it is recommended to give it the chance to hunt down its food in deep water. Unfortunately, artificial rivers are not large enough to provide for this need. Lakes and lagoons, as well as some larger natural rivers, are preferable. Cliffs are another beneficial habitat feature, since they like to perch where predators cannot reach. While the Jurassic World Aviary did not have deep enough water sources, it did provide a dynamic cliff-filled environment in which to roost.

Another challenge is keeping its habitat large enough for its population. This is a gregarious pterosaur and prefers to live in flocks, so having a large number is often favored; Jurassic World failed to make its aviary large enough for the huge flock it housed, however. This led to the pterosaurs becoming cramped, and therefore stressed. During the 2015 incident, the flock behaved very reactively, exhibiting aggression toward humans and violently attacking tourists. Such a tragedy could have been avoided by providing for the pterosaurs’ needs. However, it is also possible to overstimulate them. Too many moving targets, excessive noise, and dramatic lighting contrasts can make them agitated and are equally as bad as understimulation. There is a happy medium which must be met in order to safely and humanely keep this pterosaur in captivity.

During the park’s operation, a minor incident occurred in which a Pteranodon stole a tourist’s hat.

Science

Before Pteranodon, all the known pterosaur species were smaller toothed varieties chiefly known from Europe. This was the first major North American find, the first truly huge pterosaur found by paleontologists, and the first to demonstrate a toothless beak. This is where its name, which means “wing without teeth,” comes from. Since it is one of the most common pterosaurs in the fossil record, it has provided a wealth of information about these reptiles’ biology, including their anatomy, sexual dimorphism, evolution, and ecology. Fossils of distinct males and females, as well as different growth stages, are well-known. These pterosaurs are presumed to have been a major ecological presence in the Western Interior Seaway, a marine ecosystem which existed in North America during the middle of the Cretaceous period.

While it was the first pterosaur confirmed added to InGen’s genetic database and therefore the first pterosaur to have its genome analyzed by modern science, it has sadly not been quite as useful as a scientific model as it perhaps could have been. The first specimens were engineered in the 1990s, when paleontological knowledge about pterosaurs was not as complete as it is now, and numerous phenotypic errors were produced. Some, such as the presence of teeth in one variant, would have been obvious anomalies; others appear to have gone under the radar and are still present in modern Pteranodons. As a result, some aspects of its behavior are significantly altered. Some may have been altered by InGen on purpose for display and entertainment reasons. So, while some of its behaviors are probably similar to its ancient ancestor, any conclusions drawn from InGen Pteranodons cannot be completely applied to paleontology.

Politics

Because of its ability to fly, Pteranodon has never been possible to contain on remote islands with complete confidence and certainty, and this makes it more of a public safety risk than other de-extinct animals. Any escapes from the islands in the Gulf of Fernandez have invariably resulted in the pterosaurs migrating north along the American coastline, often taking them through inhabited regions. These are not limited to Latin America; some have been sighted as far north as British Colombia. Because of their migratory patterns and territorial behavior, Pteranodon has been an international political issue since the summer of 2001, when the first such incident was reported.

To deal with the Victoria incident, the Canadian government hired American security contractor Vic Hoskins to lead a team and neutralize the animals. His success at doing so led to him being hired by Simon Masrani to become the new head of InGen Security. Pteranodon remained out of the news for a little over a decade, but then returned in force during the 2015 Isla Nublar incident, which involved the escape of the entire Jurassic World Aviary population. The flock, already stressed from their insufficient living conditions and further agitated by the incident’s events, pursued a jeep to the Main Street area where they found a sufficient marine water source and abundant food. Unfortunately, their food items were the Jurassic World tourists and staff members. This led to a violent confrontation between the animals and park security, with the whole incident being recorded and publicized almost instantly. Scores of injuries and several deaths, both of humans and pterosaurs, resulted. It was this conflict more than anything else that ensured Jurassic World would close forever; recover from such an incident was impossible.