Stygimoloch is a dubious genus of pachycephalosaurine dinosaur, considered by some paleontologists to be synonymous with Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis. It has one named species, S. spinifer, which is known in fossilized form from the Hell Creek, Ferris, and Lance Formations in Montana, South Dakota, and Wyoming. This animal originally lived during the Maastrichtian age of the Cretaceous period, between 68 and 66 million years ago (though if it is a synonym for Pachycephalosaurus, it would actually have evolved around 70 million years ago). Because it is found in separate parts of Hell Creek, some paleontologists do still think it should be treated as its own species, though the general consensus is that this is a young adult form of Pachycephalosaurus. Its genus name is usually said to mean “demon from the River Styx,” but literally translates to “Stygian Moloch.” The River Styx, in Greek mythology, separates the world of the living from that of the dead. A being is said to be “Stygian” if it hails from this underworld. Moloch comes from the Hebrew Bible, often interpreted as a demon or sinister false god, usually associated with human sacrifice. The scientific name is a play on the fact that the dinosaur’s fossils were first found in Hell Creek, in addition to its resemblance to an archaic horned demon. The specific epithet spinifer means “spiny,” because its head is spiny.

Stygimoloch is a dubious genus of pachycephalosaurine dinosaur, considered by some paleontologists to be synonymous with Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis. It has one named species, S. spinifer, which is known in fossilized form from the Hell Creek, Ferris, and Lance Formations in Montana, South Dakota, and Wyoming. This animal originally lived during the Maastrichtian age of the Cretaceous period, between 68 and 66 million years ago (though if it is a synonym for Pachycephalosaurus, it would actually have evolved around 70 million years ago). Because it is found in separate parts of Hell Creek, some paleontologists do still think it should be treated as its own species, though the general consensus is that this is a young adult form of Pachycephalosaurus. Its genus name is usually said to mean “demon from the River Styx,” but literally translates to “Stygian Moloch.” The River Styx, in Greek mythology, separates the world of the living from that of the dead. A being is said to be “Stygian” if it hails from this underworld. Moloch comes from the Hebrew Bible, often interpreted as a demon or sinister false god, usually associated with human sacrifice. The scientific name is a play on the fact that the dinosaur’s fossils were first found in Hell Creek, in addition to its resemblance to an archaic horned demon. The specific epithet spinifer means “spiny,” because its head is spiny.

In 1983, this dinosaur was first described by paleontologists Peter M. Galton and Hans-Dieter Sues, from Britain and Germany respectively. Better fossils were discovered in 1995, as fossil hunter Mike Triebold found a more complete skeleton; originally assumed to be a Pachycephalosaurus, it was later identified as a Stygimoloch. This was the first pachycephalosaur fossil ever found with its head in association with the body, providing useful insight into how the animals’ biomechanics. Even at this early stage, Stygimoloch and Pachycephalosaurus were often confused with one another, showing a great many similarities.

In 2007, paleontologist Jack Horner suggested at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology that the smaller pachycephalosaur Dracorex (known for a flatter skull and shorter horns) might be a juvenile form of Stygimoloch, instead of being a different species, and that both of them might just be younger forms of Pachycephalosaurus. The hypothesis was also put forth that Stygimoloch fossils might represent the female of the species. Major evidence was the fact that the skulls of Dracorex and Stygimoloch were not fully developed, meaning that all the fossils known were from juveniles, while all Pachycephalosaurus fossils were adults. He and Mark B. Goodwin published this theory formally in 2009, and it was supported by Nick Longrich in 2010. Then, in 2016, baby pachycephalosaurs were discovered; they had knobs on their skulls in the same places as all three Dracorex, Stygimoloch, and Pachycephalosaurus, and had flatter skulls. The theory now is that the animals are born with flat skulls, develop longer horns, and then as they mature their horns wear down and their domes grow larger.

Not all paleontologists agree, with David Evans (originally a proponent of lumping the three genera) in 2021 suggesting that Stygimoloch might be its own genus after all. He still considered Dracorex a juvenile form. His evidence was the fact that all of the Stygimoloch fossils came from the upper part of the Hell Creek Formation, while all of the Pachycephalosaurus came from the lower part.

Sometime before 2015, Stygimoloch was cloned by International Genetic Technologies using ancient DNA recovered from Maastrichtian amber samples. InGen had previously cloned Pachycephalosaurus in the 1980s or 1990s, but their newer Stygimoloch seem to be a different variety of animal. There are two possibilities: one is that Evans’ 2021 assessment is correct, and Stygimoloch truly is a different genus. The other is that InGen scientists genetically modified Pachycephalosaurus to retain juvenile traits, calling the result Stygimoloch. Originally intended for display in Jurassic World, this animal was not yet ready for exhibition when the park closed; since then, it has been artificially introduced to the Pacific Northwest in 2018 and is now found in North America once again, as well as elsewhere in the world due to the illegal wildlife trade.

Description

Stygimoloch, like many pachycephalosaurs, is known only from partial remains. Because of this it is hard to tell how closely InGen’s specimens resemble the original animal. It is a biped, walking nimbly on two legs, and has three stout toes on each foot. The fourth toe is still present as a tiny dewclaw, serving no function in its current state. The claws on all of its digits are fairly short, but its legs are powerful. Stygimoloch can run about as fast as a human, slower than the stronger Pachycephalosaurus but still a respectable speed for a stocky animal. Its tail comprises a little less than half of its full length, which can reach 6 to 11.5 feet (1.8 to 3.5 meters). It stands about 4.6 feet (1.4 meters) tall. This dinosaur weighs between 170 and 498 pounds (77 and 226 kilograms) at its full size. Its average weight is two hundred pounds, or 90.7 kilograms, and its average length is 7.2 feet or 2.2 meters.

The anatomy of InGen Stygimoloch differs in a few minor ways from those known from fossils, an unavoidable side effect of genetic engineering. In the cloned specimens, the torso is shorter and the tail more flexible, while its wrists are able to pronate (an error common to InGen theropods as well). It has the same number of digits on its hands, but all five of them possess small claws, whereas in fossils the last two fingers lack them. Pachycephalosaur hands are made for grasping food plants and are not especially dexterous. The arms are quite short.

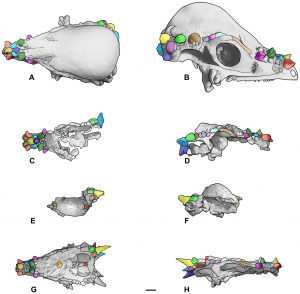

As with its relatives, the most notable anatomical feature is the skull, which possesses a cranial dome which can reach nearly ten inches (25.4 centimeters) thick. This makes its skull very heavy, so its neck is powerful to support the weight. In InGen specimens, the head is proportionally larger than its fossil counterparts; it is also decorated differently, with the spines and knobs arranged in different positions than the fossils. InGen specimens have a single horn on the nose, a collection of knobby bumps forming a V-shape up either side of the head over the eyes, bigger spikes underneath the eye orbits, and symmetrical arrangements of longer horns on the back of the head. In fossils, these horns could reach four inches (10.2 centimeters) long, but the larger heads of InGen Stygimoloch give them longer horns as well as taller domes. Having such a thick skull means that its brain is rather small, and it is not very intelligent. It has keen eyesight.

Like its ancestor, the mouth is beaked, with cutting teeth in the rear of its mouth and incisors toward the front. The mouth is highly constrained by cheeks, whereas its ancestor’s mouth is believed to have been wider. It has forward-facing eyes, giving it binocular vision, and its pupils are rectangular. This pupil shape is found in many prey animals, including goats, toads, and octopuses, and serves to protect the retina from sun glare. However, since Pachycephalosaurus has round pupils similar to those of a bird, the rectangular pupils of Stygimoloch may not be a natural feature. Its sclerae are dark orange.

Most of Stygimoloch‘s body is reddish-brown, which would serve to camouflage it among mud, wood, and rocks where it lives. The underside of its body (including the lower jaw) is cream-colored, while the upper body has darker brown stripes and patches. Its scales are rounded, with the largest ones on the face and smaller pebbly scales on the rest of its body. The feet, like those of many birds, have larger scales. On its head, the spikes and cranial dome are off-white with streaks of gray, due to being sheathed in keratin.

Growth

Younger Stygimoloch have flatter domes, resembling those identified as Dracorex. As they grow, the domes increase in height and thickness. Spikes develop on the rear of the head, serving to protect these animals from predator attacks from behind, but the spikes become shorter and rounder while the animal grows up.

In prehistory, Stygimoloch may not have been its own genus at all, and instead an adolescent form of Pachycephalosaurus. It is possible that InGen Stygimoloch never grow into their true adult forms and are engineered to remain in this sub-adult growth stage.

Sexual Dimorphism

So far no reliable way to sex a Stygimoloch at a glance has been determined. Females have been positively identified, but it may be that males and females are difficult to distinguish (at least to a human observer).

Habitat

Preferred Habitat

This dinosaur was originally native to warm habitats with abundant vegetation and rivers, and today it prefers similar habitats. It can survive in both hot and cool climates, and since it is a smaller prey animal, it seeks out environments with forest cover and other types of shelter. Open grasslands and prairies are usually not far away from its home, though, and it finds much of its food here. Speed allows it to quickly move to hide or defend itself if it spots a predator while in the open. Stygimoloch is a nimble creature capable of navigating difficult terrain, which allows it to adapt to various types of habitat in its world. Fossil evidence suggests that it could live comfortably in coastal regions.

Muertes Archipelago

There is no evidence of Stygimoloch being bred on any islands of the Muertes Archipelago. The largest island in this chain, Isla Sorna, was originally used by InGen for de-extinction research and development. However, it was abandoned in 1995, briefly revived in the late 1990s, and then mostly abandoned again, all of which took place before any known Stygimoloch were bred.

Isla Nublar

The first confirmed Stygimoloch on Isla Nublar hatched between May 16, 2010 and May 15, 2011. Stygimoloch was probably intended for exhibition in the Jurassic World theme park on the island, but was never advertised on the park website, and there is no evidence that it actually made it to the point of being put on display. The Jurassic World Cookbook describes its intended habitat as the Jungle River.

During the years preceding 2015, this dinosaur most likely lived in a designated area of Sector 5, which was restricted to visitors and housed the park’s up-and-coming or classified assets. Stygimoloch does not appear to have been common. On December 22, 2015, the park was shut down due to a security failure that caused staff deaths and tourist injuries, and the animals were permitted to roam the abandoned island facilities freely. The Stygimoloch seem to have favored the central areas of Isla Nublar, though there were many regions of the island that would have suited them.

In early 2017, the dormant volcano Mount Sibo began to show signs of activity, and as it grew more active it caused the degradation of habitats on Isla Nublar. Stygimoloch populations were also threatened by the presence of far too many dinosaurs for such a small island; the abundance of predators and competitors challenged them. In 2018, volcanic activity and overpopulation pushed many dinosaurs toward the brink of extinction. Poaching also reduced the populations, including a large-scale operation in June led by an American mercenary called Ken Wheatley. At the end of this operation, which departed Isla Nublar on June 23 as the eruption became violent, there were five remaining adult Stygimoloch: one was left behind and perished in the eruption, having been east of Mount Sibo when the area was engulfed in volcanic ash and toxic gases. Four others, including a female nicknamed Stiggy, were removed from the island via the cargo ship S.S. Arcadia and taken to the United States.

The last Stygimoloch to be logged into the Arcadia manifest was entered in at 13:51 local time and held in Container #33-1014-0071 (Cargo #22824). It was cosigned by Umberto Spatuzzi and weighed in at 80 kilograms, placing it at the smaller end of the scale for this species.

Mantah Corp Island

While the facility constructed by Mantah Corporation on their privately-owned island was home to numerous species that they illegally appropriated from InGen, there is no evidence that Stygimoloch was among them.

Biosyn Genetics Sanctuary

After their release into the wild in the summer of 2018, populations of Stygimoloch became enough of a concern to governments of the world that action was sanctioned against them and other de-extinct species. Biosyn Genetics was perhaps the most highly-regarded authority permitted to round up and contain the animals; they worked closely with the Department of Prehistoric Wildlife in the early 2020s, during which time they had exclusive rights to captured de-extinct animals.

Stygimoloch are housed in the Biosyn Genetics Sanctuary located near their headquarters in northern Italy. The vocalizations of juveniles could be heard in the Habitat Development laboratory in early 2022, suggesting there is a stable breeding population. Currently, the facility has been put under supervision of the United Nations following the exposure of systematic corruption in Biosyn’s executive ranks.

Black market

Poaching was a major problem in the Gulf of Fernandez between 1997 and 2018, though Stygimoloch is believed to only have lived on Isla Nublar where security was tighter. It is unknown if any were removed without InGen’s knowledge. The first case of Stygimoloch poaching was in June 2018; during an operation on then-abandoned Isla Nublar, mercenary hunter Ken Wheatley captured at least four adult Stygimoloch at the behest of financier Eli Mills. They were intended to be sold on the black market, being delivered to Lockwood Manor during the night of June 24, but were instead released after the auction was disrupted by animal rights activists. However, a case of genetic samples including this species was sold to a Russian buyer, most likely the mobster Anton Orlov.

One adult Stygimoloch was rescued by Costa Rican authorities in early 2022, having been found in a vehicle in San José during a traffic stop. It was presumably relocated to the Biosyn Genetics Sanctuary or some other designated dinosaur habitat. This animal does not grow exceptionally large, making it easier to smuggle; it is likely that it has been trafficked around the world, as has its DNA. Because of the covert nature of such trades, the exact number and locations of Stygimoloch assets cannot be determined, but a large number probably pass through the Amber Clave night market which operates at clandestine locations in Valletta, Malta. In early 2022, at least one juvenile was confirmed being held by animal traffickers in one of the Amber Clave’s major locations. Since this location was exposed and infiltrated by intelligence agents, some of the animals there may have been rescued.

Wild populations

Stygimoloch originally inhabited North America, particularly the western region of the continent, and seems to have lived around rivers and coastlines of the Western Interior Seaway. This inland ocean was in the process of receding toward the end of the Cretaceous period. Skulls of pachycephalosaurs are often found isolated from the rest of the skeletons, which led some paleontologists to suggest they inhabited mountains and their heavy skulls would roll downhill after their bodies decomposed; however, more complete Stygimoloch skeletons are known. This dinosaur had evolved by around 68 million years ago. At the very end of the Cretaceous, a mass extinction event wiped out Stygimoloch and nearly all of the other dinosaurs.

Sixty-six million years later, scientists discovered ancient DNA samples in sources such as amber inclusions that allowed them to reconstruct parts of prehistoric genomes. Stygimoloch was among them, though one hypothesis suggests that it was genetically modified from Pachycephalosaurus to retain adolescent traits and never grow into its full adult form. After some years of living in isolated facilities off the Central American coast, this dinosaur was brought to Orick, California on June 24, 2018 where it was housed in Lockwood Manor to be illegally auctioned off. One of the four, a female called Stiggy, was released by Dinosaur Protection Group activists; the other three were released later that night by Maisie Lockwood in order to save them from hydrogen cyanide poisoning. All four fled into the woodlands near Orick. These dinosaurs seem to have migrated and spread throughout western North America since then, suggesting that some of the rescued animals were males and that they bred in the wild. In 2021, the CIA’s dinosaur tracking division began monitoring a Stygimoloch population on the Llano Estacado of West Texas. As of early 2022, they had been reported in the U.S. state of Colorado, near the New Mexico border. The game Jurassic World: Evolution 2 portrays a small population having established itself within Yosemite National Park in California, southeast of where they were released. Their adaptable nature and toughness likely aid them in finding footholds in the strange new ecosystems where they now live.

While most Stygimoloch still inhabit North America, the black market has brought many elsewhere, and they often escape when not properly contained. A population exists near the marshy remnants of Lake Poopó in Bolivia, and is currently the only group of these animals in South America.

One adult was suspected to inhabit Seoraksan National Park in South Korea in 2022, presumably having been transplanted there by human intervention, and was eventually caught on a trail camera. During the previous year, the CIA had tracked two previously confirmed Asian populations, one in China’s Altun Shan mountain range and one in the red-sand ergs of An Nafud in Saudi Arabia.

Some have also been sighted in Africa, where they have become a part of local food webs. The CIA has monitored a population near Brandberg Mountain in Namibia since 2021, likely using the nearby river valleys to survive the conditions of the coastal Namib Desert. In early summer 2022, wildlife cameras in Nairobi, Kenya caught footage of a pride of lions hunting a lone Stygimoloch at night; greatly outnumbered, this animal probably did not survive the encounter.

A sick individual was discovered in Beerburrum, Queensland in mid-2022 and taken in for shelter by locals, before being surrendered to a local paleo-sanctuary for treatment. It is unknown if it still lives in an Australian sanctuary or if it has been transported elsewhere.

Behavior and Ecology

Activity Patterns

Stygimoloch is diurnal, meaning it is active mostly during the daytime. Its rectangular pupils aid in protecting its eyes from sun glare, an adaptation found in a few species of diurnal prey animals. In areas with human activity, some Stygimoloch have taken to coming out mostly at night, rather than during the daytime, a behavioral change that had been observed in numerous modern animal species already.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

The incisors and cutting teeth of this dinosaur aid it in feeding on softer foods, such as ferns, leaves, fruits, and seeds. It is not well-adapted for eating fibrous plants. In the prehistoric animal, it is assumed that its cheeks were quite reduced and that it had a wider mouth than its modern counterpart, since InGen’s pachycephalosaurs have large cheeks similar to a mammal rather than a dinosaur. These cheeks restrict the size of food it can bite, making it into more of a selective feeder than it may originally have been. However, it can fit more food in its mouth using these cheeks. It uses the serrations on its teeth to shred food. An adult Stygimoloch consumes ten to twenty pounds of food a day, up to ten percent of its average body weight.

In addition to ferns and other soft plants, this dinosaur will feed on the roots of trees and shrubs. This means it must dig for its meals, likely using the horn on its nose or its strong feet to plow through dirt. Sometimes it may dig rather deep to find buried roots to feed on. Its mouth is not adapted for eating wood, so instead it probably targets the tender tips of roots which are still soft and easily bitten through.

Some scientists speculate that pachycephalosaurs like Stygimoloch may be omnivorous, feeding on eggs, carrion, and small animals such as insects or lizards to supplement their plant diet. These would be useful sources of protein for this animal, which relies on muscle to survive. It is an experimental feeder and may test unfamiliar objects to see if they are food. Because of this it can be seen eating garbage in urban or suburban areas.

The game Jurassic World: Evolution suggests that its diet consists mostly of horsetails, and that it also prefers grasses and cycads. It is unable to properly digest tree ferns, conifers, and ginkgo leaves. The sequel to this game portrays it feeding mostly on low-growing leafy vines.

Social Behavior

Stygimoloch is a reclusive dinosaur that mostly keeps to itself, but lives in small groups for protection. They seem to be able to survive in groups of three at least, not forming large herds, and not much has yet been observed of their lives. The horns on their heads serve mostly a defensive purpose, but may also be used to display or signal to each other. Conflicts, probably over dominance and mating rights, are settled by head-ramming. The high domed skull of Stygimoloch is built for delivering solid blows to a rival. While their heads can be knocked together, their ramming attacks are most effective when they hit the flank of a foe. A fight ends when one contestant gives up. To withstand impacts, the neck of Stygimoloch is sturdy and strong.

These animals are not very intelligent, so their social lives are probably not complex. They are shown in Jurassic World: Evolution 2 to rub their domes together when affectionate, although these social interactions can quickly turn into brief headbutting matches.

Reproduction

Little is known about how this dinosaur reproduces, as eggs have yet to be seen. It appears they can attain maturity in less than seven years, at least when under the effects of InGen growth accelerators. Juvenile pachycephalosaurs are believed to have flatter skulls than adults, and their horns round out as they grow; therefore, younger animals have flat heads and long horns while adults have round domes and shorter horns. The parental behaviors of Stygimoloch have not yet been observed in detail, but virtually all dinosaurs are quite protective of their young.

Courtship most likely involves displays of strength, since this is what helps the animal survive. In males, the thickness of the dome and size of the horns probably plays a role in being attractive to females. Eggs are laid in ground nests built out of soft foliage; the eggs themselves are ovoid and brownish, like those of many ground birds. Clutches of around five eggs seem to be normal. Smaller dinosaurs like this one usually have incubation periods that last weeks to months.

Communication

As befitting an unintelligent creature, the methods used by Stygimoloch for communication are short and to the point. It can often be heard making grunting and snorting sounds, even when by itself. These sounds may be used to keep in touch with other members of its social group, or to express its mood. When agitated, they will squeal loudly; they interpret high-pitched noises as a challenge. Stygimoloch will also growl at rivals and enemies to intimidate them.

Body language is also important in this species, since it has a prominent visual display on its head. When a Stygimoloch faces a foe, it will wave its head around to show its domed skull. This makes its intentions clear and may give an enemy second thoughts about fighting. However, if challenged, it will often charge without warning first. Once in combat, it will then make intimidation displays before furthering its attack.

Ecological Interactions

Rarely seen and quick to flee from danger, Stygimoloch does its best to avoid notice from larger animals in its environment and seldom interacts with other species. It is wary around other animals, particularly those that can cause it harm. On Isla Nublar, it lived in habitats alongside numerous predators, including Allosaurus, Dilophosaurus, Teratophoneus, Compsognathus, Baryonyx, Carnotaurus, Pteranodon, Tyrannosaurus, and Velociraptor. As a mid-sized prey animal, it would have been vulnerable to many types of predators; the smallest of these, Compsognathus and Velociraptor, were likely those it could best defend against. If unable to escape, a Stygimoloch will use its domed head to ram an attacker. It can flip a smaller enemy into the air if it is able to get its snout underneath the foe’s body. When attacked from behind, it will use the horns on its head to protect its neck.

In the modern day, this dinosaur lives among predators that it would not have encountered on Isla Nublar. Here it finds an unusual weakness: its vocalizations sound similar to those of pigs or dogs. Animals that hear these may mistake its cries for these domestic animals, which are commonly preyed upon by medium-sized and large mammalian carnivores. This can get a vocal Stygimoloch into unexpected trouble, which it must defend against. Since they have been transplanted into a wide range of environments, they may be preyed upon by surprising hunters such as lions in Kenya.

Many herbivorous dinosaurs also can be found living alongside Stygimoloch. It is tolerant of these neighbors, but is still cautious; many of them could be potential competitors and are dangerous in their own ways. Its close relative Pachycephalosaurus was known from similar habitats on Isla Nublar. Ceratopsians, which are more distant cousins to the pachycephalosaurs, also favor similar territories: it has been recorded living near Triceratops, Nasutoceratops, Microceratus, and Sinoceratops. They must be wary of Triceratops, which are territorial and known to harass other herbivores. Armored dinosaurs, including Stegosaurus, Peloroplites, and Ankylosaurus, may live in the same forests, as do the hadrosaur Parasaurolophus and the omnivorous ornithomimid Gallimimus. Its biggest neighbors are sauropods, such as Apatosaurus and Brachiosaurus; these animals provide a benefit, since they are often the first to spot danger.

Since it is mostly herbivorous, Stygimoloch does not usually threaten other animals in its habitat. Instead, it preys on plant life, feeding on the low-growing soft plants found on forest floors and riverbanks. Stygimoloch can survive on grasslands but also likes forest areas to shelter within, benefiting from the presence of large trees to hide from its many predators. It has been successfully acclimated to several types of forest, ranging from tropical cloud forest to temperate redwoods. Since it eats only ground plants, being unable to reach very high, it must stick to places where enough sunlight reaches the forest floor in order for its food to grow. It does not eat tougher woody plants, so young trees are generally left unharmed by its feeding. However, it may eat the ends of roots, which can damage plants and lead to disease. It eats fruits and seeds, which can help to disperse some plant species.

As with all animals, it is bothered by pests such as mosquitoes. In the Cretaceous period, blood-feeding invertebrates were known to bite it, and their modern counterparts likely do as well. These pests can spread disease in the form of bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms. Stygimoloch is also not fond of bees and will avoid them. According to Jurassic World: Evolution, this dinosaur species is particularly susceptible to infections of Campylobacter, a bacterium which causes the disease campylobacteriosis.

Cultural Significance

Symbolism

A relatively obscure dinosaur among laypeople, the Stygimoloch was featured often in paleoart until somewhat recently. It was suggested to be a juvenile form of Pachycephalosaurus, and since has come to illustrate the uncertainty inherent in scientific reconstructions of such ancient organisms. Since it has been cloned by InGen, it also represents the fundamental alterations to nature that genetic engineering and de-extinction cause. It is not known whether InGen’s Stygimoloch is a naturally-occurring species, or if it was engineered to retain juvenile traits. This species did not make it to display for the public before Jurassic World closed, so it has stayed mostly out of the public consciousness. Pachycephalosaurs in general are often considered symbolic of stubbornness and ignorance due to their low intelligence and bad temperament.

According to Universal Studios, Stygimoloch is the dinosaur of the Cancer astrological sign (June 21 – July 22).

In Captivity

Although pachycephalosaurs can be a handful, they do have a silver lining as far as captivity is concerned: they are not terribly smart, and therefore easily outwitted. Keeping them in captivity is not a difficult endeavor as long as their needs are met and their comfort is sufficient. It is probably advisable to keep Stygimoloch under similar conditions to its relative Pachycephalosaurus. Ample space to run, places to shelter when they feel stressed, and readily-available soft plants and fresh water should do for their habitat. Sturdy containment measures should be put in place: while this dinosaur did not make it to exhibit in Jurassic World before the park closed, double-thick glass was used in its paddock walls, which deterred escape attempts. Its intended habitat was the Cretaceous Cruise, which would have presented a challenge for keeping it contained; this may have been why its introduction was delayed. Some amount of stimulation is necessary, as with all animals. Though they are not bright, they still need ways to entertain themselves. Stygimoloch, like its relatives, enjoys bashing things around; give it sturdy objects that it can ram or swipe.

Keeping it happy is the key to avoiding major headaches, both for keepers and the animals themselves. If they are not satisfied, they will quickly begin ramming other things: their paddock-mates, animal handlers, or restraining technology. This can lead to damage to the paddock or injury to people and animals. Even the Stygimoloch themselves have limits. While their heads and necks are built for withstanding strikes to rivals and predators, they never evolved for modern inventions such as metal and concrete. In addition, park staff who are prone to whistling idly should probably be assigned to other species; Stygimoloch seems to interpret high-pitched sounds as a challenge to fight.

Science

Stygimoloch holds significance in paleontology due to the historical questions regarding its identity. Fossils of this animal were often identified as Pachycephalosaurus remains, though the skulls were clearly visually different. However, scientists began to realize that only juvenile Stygimoloch were being discovered, and only adult Pachycephalosaurus were known, despite the animals living in the same place at the same time. Eventually it was proposed that they were not two different dinosaurs at all, but rather different growth stages of the same animal. Most paleontologists now agree with this assessment. This has been applied to other types of pachycephalosaurs as well; it is believed that they go through distinct ontogenic changes, with juveniles having flatter domes that increase in height as they age while their horns become smaller and more rounded.

This posits questions about the identity of InGen’s Stygimoloch, which was cloned in the early 2010s not long after the proposal that it was a synonym of Pachycephalosaurus. One possibility is that this dinosaur actually is a distinct species after all. Another is that, as with some of the other Jurassic World dinosaurs, Stygimoloch was created through genetically modifying an existing species. InGen had already cloned Pachycephalosaurus in the 1980s or 1990s, so it is not impossible that their scientists modified that animal’s DNA to result in a creature that would retain juvenile pachycephalosaurid traits even as it matured. This process, the retention of juvenile traits, occurs in nature and is called neoteny. Whether the InGen Stygimoloch is neotenous on its own or due to genetic modification is a subject for the minds of the Genetic Age to study, and in either case, it will yield interesting data on pachycephalosaur biology. The evolutionary genetics of these often-neglected creatures is a fascinating field of research.

Politics

Paleontological debates aside, Stygimoloch is not an especially controversial dinosaur since it has not publicly had a moment in the spotlight. Like the other Isla Nublar animals, its survival was put up for debate in the late 2010s when the island’s ecosystem came under threat of extinction. If the volcano Mount Sibo continued to increase in activity, the dinosaurs would die out. Advocating for the dinosaurs’ rescue was the goal of the Dinosaur Protection Group, led by former Jurassic World administrator Claire Dearing; however, she and the DPG were staunchly opposed by the U.S. government, Masrani Global corporate representatives, environmentalist groups, and anti-science activists. Such broad-spectrum opposition was not matched by an equally unilateral response from the animal rights movement, and in 2018, the decision was made to let the animals go extinct.

Paleontological debates aside, Stygimoloch is not an especially controversial dinosaur since it has not publicly had a moment in the spotlight. Like the other Isla Nublar animals, its survival was put up for debate in the late 2010s when the island’s ecosystem came under threat of extinction. If the volcano Mount Sibo continued to increase in activity, the dinosaurs would die out. Advocating for the dinosaurs’ rescue was the goal of the Dinosaur Protection Group, led by former Jurassic World administrator Claire Dearing; however, she and the DPG were staunchly opposed by the U.S. government, Masrani Global corporate representatives, environmentalist groups, and anti-science activists. Such broad-spectrum opposition was not matched by an equally unilateral response from the animal rights movement, and in 2018, the decision was made to let the animals go extinct.

Four Stygimoloch were illegally removed from the island by the Lockwood Foundation on June 23, 2018 and transported to the Lockwood estate in Orick, California. This was orchestrated by the Foundation’s manager Eli Mills, acting against the wishes of his employer (who had hoped to relocate the animals to a privately-owned island). The dinosaurs were intended to be sold on the black market to finance clandestine genetic research. However, the auction was disrupted by the DPG, and the apparent leader of the Stygimoloch played a key role in this. The dinosaur, an adult female named Stiggy and one of the first of her kind to be cloned, was goaded into damaging the holding cells of the manor’s laboratory and set loose into the auction hall. She provided a distraction necessary for the DPG to avoid manor security and bring the auction to a halt. The other three Stygimoloch were released later that night, as the conflict had caused a gas leak that threatened their lives. Today these dinosaurs have established a small but firm foothold in North America, and their fate is now decided by a multitude of governmental, corporate, and private interests who seek to capture and control them.

Resources

Unfortunately, this dinosaur did not make it to exhibit in Jurassic World, the park having closed before it had the chance. This means its potential as a park attraction is unknown. However, its unique appearance and exciting demonstrations of intraspecific combat are points in its favor. Possibly due to genetic engineering, it retains a “cute” juvenile-like appearance as an adult, which further enhances its appeal. In the wild, it can be an economically damaging species as it feeds on the roots of plants both in nature and on cultivated land. This damage can lead to disease infecting the plants, potentially resulting in crop loss.

Stygimoloch, like many dinosaurs, also has use in the pharmaceutical sector. Having been extinct since the Cretaceous period, its biochemistry is unlike modern animals, meaning it is a source of unique biopharmaceutical products. It has been targeted for this purpose since 2018, with companies including Aldaris Pharmaceuticals and BioSyn Genetics seeking to acquire it. Stygimoloch, or even just samples of their DNA, are expected to fetch high prices; this was why they were captured during the 2018 operation on Isla Nublar by mercenary Ken Wheatley. While none of the four captured animals were successfully sold, they would have generated profit to fund Henry Wu‘s research. Other dinosaurs in the operation sold for amounts in excess of ten million U.S. dollars per animal.

As demonstrated during the illegal auction at the Lockwood estate, a Stygimoloch may have other, more unconventional uses. Its strength, determination, and stubborn pigheadedness mean that it can be easily enticed into attacking, damaging barriers and generally causing havoc. Animal behaviorist Owen Grady used his knowledge of the animal’s behavior to trick it into breaking down a brick-and-mortar wall, breaking a locked cage door, and attacking security guards. While this is not really an advisable strategy in most situations, an agitated Stygimoloch certainly does make an effective (if very volatile) distraction.

Safety

For the most part Stygimoloch is only moderately aggressive and does not often attack. It is a cautious, wary animal, with its offense capabilities chiefly used for fighting among its own kind. But, if a Stygimoloch chooses to fight, there is not much you can do to stop it. These are stubborn, unintelligent animals, and if one gets into its tiny mind that you are something it should charge, your best move is to simply get out of its way as fast as you can. It will probably make a sudden, headlong rush; if you are lucky, it may warn you by squealing or pawing the ground before it charges. This is your moment to sidestep or get behind shelter. If you sidestep, be prepared to do this a lot, since Stygimoloch is nimble and fast on its feet. It is able to make tight turns and has good stamina. Hiding behind something sturdy is a better idea, though ensure that whatever you hide behind is fastened down or very heavy.

If it manages to hit something, a Stygimoloch will take a moment to recover from the strike before attacking again, and may give more warning signs at this point. Now, you can make a fast and cautious retreat to somewhere safer, such as inside a building or vehicle. Do not turn and run, as this could provoke it. Back down as though the creature has won its fight, and you may lead it to believe it has. This is especially effective if the dinosaur is winded from its attack. If it has rammed something very solid, like a rock or a metal structure, it may be dazed and need a moment to recover. However, if you fail to avoid its attack, try and ensure that it rams you where you are least vulnerable. Shield your head and chest, and try to sustain a glancing blow rather than a head-on collision. Another attack the Stygimoloch may attempt is to plant its snout under your hips and flip you into the air. Protect your head from impact if this happens, and try to roll out of your fall to avoid injury.

Often, the dinosaur will flee after it succeeds in knocking you down. It is not really interested in fighting you, but rather wants to put down a threat so it can get away. Once it is gone, treat any wounds you may have. Its horns can cause lacerations, and it may strike with enough force to break bone and cause serious bruising. The best way to avoid all this is to do your best not to antagonize the Stygimoloch at all. As discussed above, they are not very smart and may easily be taken by surprise. They are an unfortunate combination of easy to startle and difficult to intimidate, so try to keep your movements slow and predictable around them. If you see one in the wild, keep your distance, and remember that they live in small groups; there are probably more around. Avoid making any high-pitched noises such as whistling or screaming. These are apparently similar enough to the squeals an agitated Stygimoloch makes, so you could end up accidentally challenging one to a fight.

This dinosaur can become a nuisance on cultivated land, feeding not only on fruit and leaves but on the roots of woody plants. It may dig up cropland to find food, and damages trees and shrubs by chewing on their roots. If you own a farm and wish to keep this dinosaur away, the Department of Prehistoric Wildlife recommends installing beehives. Stygimoloch instinctively avoids bees, making them an effective deterrent that also benefits native plant life.

Behind the Scenes

In 2009, Jack Horner and M.B. Goodwin published a paper with documented evidence to support their belief that Stygimoloch, along with the Dracorex, were not individual genera but in fact different stages of a Pachycephalosaurus‘s growth. There paper noted that the spike, or node, as well as the skull domes of all three species had extreme plasticity, meaning they were very easily shaped or molded. Another point of evidence they made was that both Dracorex and Stygimoloch had only been found in a juvenile form, while Pachycephalosaurus had only been found in adult form. They also made note of the fact that all three lived in the same locations. This, along with further research done by Nick Longrich in 2010, has led the paleontological community for the most part to believe that Stygimoloch and Dracorex were simply juvenile forms of Pachycephalosaurus, and not their own individual genera. Some years after the dinosaur was introduced to the film franchise, newer research supported the idea that it was indeed a legitimate genus, not a juvenile form, with David Evans reporting in 2021 that while Dracorex was likely a juvenile animal, Stygimoloch was a grown adult and not the same creature as Pachycephalosaurus.

This dinosaur’s inclusion in 2018’s Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom was challenged by Jack Horner, who has acted as a paleontological consultant for most parts of the franchise. According to his own word on Twitter, “It was the one thing I asked to have changed when I read the script, but someone had their mind made up.” Despite Horner’s opposition, more recent research has actually suggested the films may be correct in depicting Stygimoloch and Pachycephalosaurus as two different animals.